Introduction

When I was first starting out in bird photography, I decided it would be useful to collect some stats regarding the types of equipment used by professional bird photographers -- things like the focal lengths, how often they use teleconverters, and what f-stops and shutter speeds they were using. It turned out to be a fairly large undertaking, so I decided to limit my analysis to just one very prominent individual. In order to protect the innocent, I'm going to refer to this individual using a pseudonym instead of his real name. I will call him Lester Birdmore -- Les for short.

Les Birdmore is an extremely successful and popular bird photographer -- perhaps the biggest name in the business. And he always publishes all the camera settings with every photo, making my data collection task relatively easy. I was most concerned with focal length at the time, since I was in the market for a new telephoto lens, and I wondered how much lens was enough. I didn't like what I found out (as you'll see).

In the course of my data collection I was able to obtain a total of 134 data points. Each point corresponds to a single photo, for which the focal length, aperture, shutter speed, and whether a teleconverter was used, were all available. I also noted whether the subject was large (i.e., heron or goose-sized), medium (duck or shorebird-sized), or small (warbler-sized), and whether or not the bird was photographed in flight, or was instead stationary (meaning not in flight -- even if the bird was walking or flapping the wings).

Most of the photos were of stationary birds; only 16% were flight shots. Also, fully half of the shots were of large birds such as herons, egrets, storks, or geese. Only 20% of the photos were of warbler-sized birds, and nearly all of those were stationary. Thus, it can be said that Les Birdmore prefers to photograph large birds that aren't moving very fast. This should be kept in mind when interpreting the data below, since the ideal equipment and camera settings for warblers or flying birds may differ somewhat from the biases uncovered in this analysis.

The Numbers

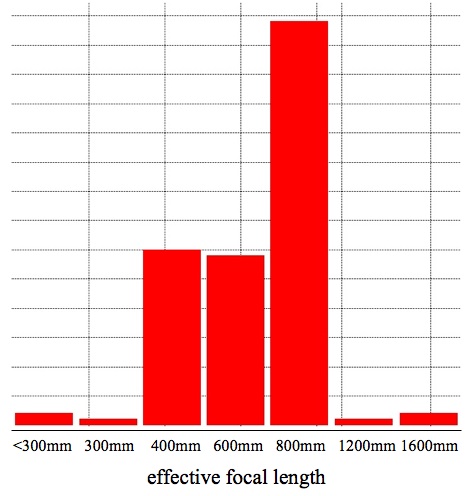

Let's begin with the focal length. Since I'll be presenting information on the use of teleconverters (TC's) below, for now we'll restrict our attention to the effective focal length, which takes any teleconverter into account. Thus, an effective focal length of (approximately) 800mm corresponds to the use of an 800mm lens or to the use of a 600mm lens fitted with a 1.4x teleconverter.

The graph below shows the results. This graph is a histogram, so the height of each bar indicates frequency. As you can see, the most commonly used focal length by Les Birdmore for these 134 photos was roughly 800mm. These consisted of a roughly even mix of 600mm+1.4x TC shots and 800mm prime-lens shots. The 800mm category is therefore an extremely useful one for bird photography. The second and third-place focal lengths were 400mm and 600mm, yet even these combined do not add up to the frequency with which an (approximately) 800mm focal length was used. Outside the 400-800mm range, very few other focal lengths were used at all. A few shots taken using teleconverters were in the 1200-1600 range, but these were very rare (probably due either to image degradation from the TC or to the lack of autofocus capability for those focal lengths).

Summarizing this graph numerically, the average (effective) focal length was 680mm, with a range of 40mm to 1680mm. A striking feature of the above graph is that focal lengths of less than 400mm were also very rare -- probably because at these focal lengths there simply isn't enough magnification to get a pleasing image of a bird, even a large bird like a heron or egret. Thus, for real hardcore bird photography one really needs at least 400mm, and ideally one should have 800mm, either in a prime lens or via the use of teleconverters. Unfortunately, these lenses are all expensive. Bird photography ain't a cheap hobby.

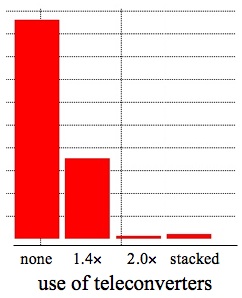

Next, let's look at Les Birdmore's use of teleconverters. From the histogram below you can see that most of his photos were taken using only a prime lens, with no TC attached. A significant number, however, were taken using the 1.4x TC. Most of these involved the 600mm prime lens, in order to reach an 840mm effective length. The 2.0x was rarely used, though it was (very occasionally) stacked on top of the 1.4x TC when enormous focal lengths in the 1200mm or 1600mm range were needed.

The use of large focal lengths (whether achieved with or without TC's) for bird photography isn't surprising -- birds are mostly small animals, and they usually don't let you get very close. For those who've already invested in a large lens, the more burning questions become those regarding how best to use the thing -- i.e., what aperture to use, what shutter speed, etc.

Les Birdmore is a very fortunate photographer, in that he has access to all the best Canon lenses. His big 600mm lens has a maximum aperture of f / 4. My own big lens is an 800mm monster with a maximum aperture of f / 5.6. One thing I've been struggling with recently is knowing how best to set the aperture under conditions of plentiful sunlight. Using a fast aperture like f / 4 or f / 5.6 allows the use of faster shutter speeds, which tends to be useful for fast-moving subjects like birds. Unfortunately, those large apertures can also result in paltry depth-of-field, which manifests itself in images having partially out-of-focus subjects.

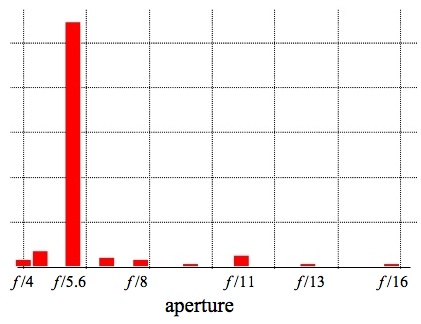

The graph below shows a clear bias in Les Birdmore's aperture settings.

As seen in the graph above, Les prefers overwhelmingly to shoot at f / 5.6. When shooting at ~800mm (600mm x 1.4), this would be the largest aperture available to him -- i.e., "wide open". Although some bird photographers like to stop-down a few f-stops to improve depth-of-field, Les typically doesn't, even though he generally shoots large birds. This may be because Les is often some distance from the bird -- for a given aperture, depth-of-field increases with distance to the subject. Another reason many users of large lenses often stop down to f / 8 or smaller is that some lenses (particularly 3rd-party lenses) are not at their sharpest wide-open, so that stopping down a bit increases lens sharpness. Les, who uses only the finest Canon lenses, apparently doesn't have that problem. I guess it doesn't suck to be Les.

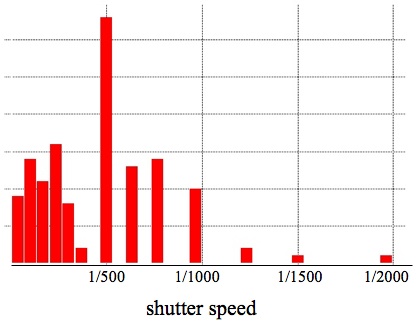

Finally, let's look at Les' typical shutter speeds:

From this graph we can see that much of Les' work is done in the 1/500 sec range. I was surprised to see that even with his big lens (which should be good for collecting light) he doesn't always shoot at 1/800 or 1/1000 or faster (though he sometimes does). Even more surprising is the mass of relatively slower shutter speeds evident in the leftmost part of this graph. Here we can see that Les does a fair amount of work in the 1/50 to 1/250 range. This may be due to the fact that Les enjoys photographing birds at dawn and dusk, when sunlight is not plentiful. Many of Les' lenses feature Canon's image stabilization (IS) technology, which tends to reduce the effects of camera shake (though not bird shake) at slow shutter speeds, such as those which would be used at dawn and dusk.

Conclusion

Much can be learned, in any field, by studying the masters. Les Birdmore, as one of the most popular and successful bird photographers in the world, is clearly a master. Like a master in any field, he has access to the finest equipment, and has spent long years perfecting his technique. Much of that technique likely cannot be quantified via histograms and averages, as we have tried to do here. Nevertheless, several useful bits of information emerge from the analyses above.

First, for serious bird photography, one absolutely needs a lens (or lens/TC combination) having a focal length of at least 400mm, and more preferably one of 800mm. While shorter-focal-length lenses may occasionally prove useful in capturing images of birds, I can say from my own experience that these are not ideal as general-purpose birding instruments. Analysis of Lester's portfolio and preferred arsenal supports this point.

Second, while much of Les' work is carried out without the use of TC's, he is not afraid to sometimes resort to the use of a sharp 1.4x converter. Only rarely does he use the 2.0x TC. My own experience with 2.0x TC's has not been good, and the general consensus seems to be that 1.4x TC's tend to degrade image quality less than 2.0x TC's do.

Finally, Les Birdmore's portfolio demonstrates that publishable images of large birds can be consistently obtained at f / 5.6, despite the relatively narrow depth-of-field induced by such a large aperture. However, since Les uses only the finest (and most expensive) Canon lenses, this doesn't necessarily mean that third-party lenses can be as easily used at such apertures to consistently obtain sharp images. I've noticed with my Sigma 800mm prime lens that images come out more consistently sharp when shooting at f / 8 than at f / 5.6, and others have noted this as well for this lens model. One also needs to take into consideration the quality of the autofocus function in the camera one is using. Les uses only professional-grade camera bodies (such as those in the Canon EOS 1D Mark II and Mark III series), which run in the $3500 to $8000 price range. These pro bodies tend to have finer autofocus capabilities, which at f / 5.6 could be critical in making sure the subject fits well into the narrow depth-of-field. In addition, cheaper cameras sometimes go out of calibration, causing the focuser to use an incorrect focus plane, so that the user has to stop down to improve depth-of-field and recapture the intended focal point. Thus, it may be important to have an expensive camera as well as an expensive lens when shooting small birds at a distance. As I said before, bird photography ain't a cheap hobby.