|

You

can be pretty sure

you’ve entered the realm of photographic

insanity when you find

yourself buying camera lenses that cost half as much as your car.

A cocaine addiction would

probably be cheaper. Nevertheless, for those of

us suffering from a severe obsession for photographing birds, there is

no closer approach to Nirvana than that achieved with the acquisition

of a super-telephoto lens of gargantuan proportions—a lens such as

the Sigma 800mm f/5.6 EX DG

APO HSM, otherwise known as the Sigmonster.

Cute name,

right? Well, make no mistake about it: this thing is freaking

HUGE.

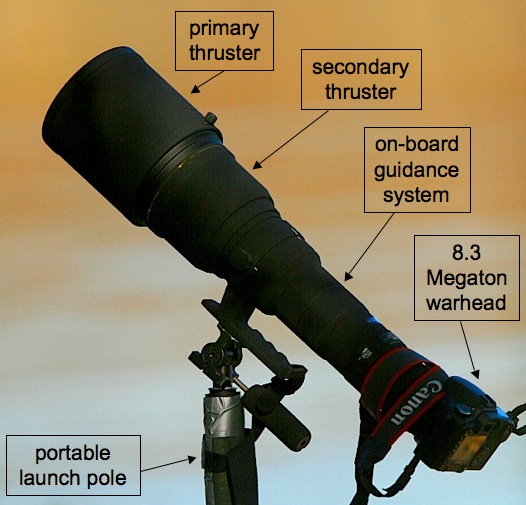

I can still remember the day it arrived on my doorstep. I frantically slapped a camera onto the beast and pointed the seething terror out the front door as the last rays of winter sunlight were fading from the sky. The birds literally cringed when they saw it...  “Holy crap! That guy’s pointing a nuclear missile launcher at me!” This

lens weighs over 11 lbs, measures 23 inches in length, and is nearly 6

inches in diameter. You don’t wear this kind of lens around your

neck. It has to be kept on an extremely sturdy tripod, which only

adds to the total weight of your gear in the field. Carrying this thing

around all day can be excruciating. At the end of a long day of

birding with this thing I barely have the energy to flop down on the

couch with my laptop and review the images captured with it.

Fortunately, images captured through the Sigmonster can often be truly stunning. Here’s an osprey chick munching on one of his very first self-caught fishes at a lake in central North Carolina: This

osprey was fairly high in a tree on the shore of the lake (see the

photo below). For this shot I had the Canon 1.4× Extender

EF II

teleconverter attached, giving an effective focal length of 1120mm

(!). You can see that even with a teleconverter attached and at a

considerable distance, the lens is capable of producing very sharp

images. Even manually focused.

Just to give you a frame of reference for the above shot, the photo below shows how far away I was from the bird (the osprey in the photo above was actually perched higher in the tree for that shot than the bird shown below):  Notice

the dog in the photo above. Normally when I go into the field I

carry not only the Sigmonster, but also a tripod over one shoulder, a

separate 560mm rig on my other shoulder, a pair of 10x binoculars

around my neck, a bag of extra lenses, and a labrador retriever on a

leash mounted on my belt. So, while the Sigmonster can

indeed be

quite an encumbrance, with enough dedication it is possible to carry

both it and all the other equipment you need into the field. You

get used to it.

So, what about small birds, like kinglets and warblers? Here’s a White-eyed Vireo I shot with this lens:  For

birds this small you do have to be quite close, even with an 800mm

lens. For this shot I used a 25mm extension tube to reduce the

minimum-focus distance of the lens, which normally is about 18

feet. For warbler photography this is usually too long.

With the extension tube I can focus to probably 10 feet or so.

An

even smaller bird than the White-eyed Vireo is the Ruby-crowned

Kinglet. I caught the following individual foraging for nectar in

a tree that was just putting forth its first blooms in mid-February:

Click on any of the thumbnails below to see more warbler-sized birds photographed with this lens: OK, but, can

this lens be used for birds

in flight?

Absolutely. Here’s a recently-fledged osprey chick catching what I believe is one of his or her first fish at a lake in central North Carolina (I observed this chick from egg to fledging):  Here’s

another shot of an osprey chick (probably the same one) in flight,

showing that sharp images can indeed be obtained from moving subjects

with this lens:

Note,

however, that getting sharp flight shots with a lens of this size and

weight virtually requires a

gimbal-type head, such as the one shown below:

A gimbal head works like a see-saw—when the lens is properly mounted (so that its center of gravity is centered over the mounting plate), it will stay in any position you like without having to hold it there. Thus, while mounted on the tripod the lens is effectively weightless, so that using it is relatively effortless (except when contorting your body to focus the thing on a bird in an exceptionally high tree). Gimbal heads tend to be expensive. The most popular one is the Wimberley, which runs about $600. I opt instead to use the much less-well-known Manfrotto gimbal head shown in the photo above, which runs about $180 [UPDATE: I’ve recently switched to using the Wimberley]. For a tripod I have used the Gitzo “Explorer” as well as the Induro carbon-fiber tripods, which tend to be expensive ($200 or so) but are both strong enough to support a lens of this size and lightweight enough to carry in the field without undue stress. Unfortunately, one of the legs on my Gitzo Explorer snapped off in the field (I was lucky enough to catch the Sigmonster before it hit the stone path). The Induro carbon-fiber replacement is better anyway, since it is much lighter [UPDATE: One of the legs also snapped off of the Induro, almost destroying my lens. I now use an $800 Gitzo carbon fiber lens, which is far better].  So, what (apart

from the size and weight)

don’t I like about this lens?

There

are a few things. First, there is the issue of build

quality. For the most part, this thing has been rock solid.

And I mean rock solid.

For nearly a year I have carried this thing into the field every

weekend for 8-hour to 10-hour days. It has been my constant

companion,

delivering sharp images upon demand, despite my whacking it

inadvertently against tree branches, car doors, and thick Labrador

skulls.

It did, however, develop a pretty serious problem after the first six weeks—the mounting ring became extremely loose, allowing the focus plane to vary wildly so as to give me quite a number of partially out-of-focus images. For several weeks I depended crucially on an extensive rig of thick rubber-bands to keep the mounting ring properly in alignment—not exactly what I would expect from a $6000 lens. After the spring birding season had died down I sent it in to Sigma for repair, which they gladly did under the terms of the warranty—i.e., for free. In about 10 days I had my beloved lens back, though the insured shipping for this $6000 item cost me well over $100.  This

lens comes with a very nice padded case, though I rarely use it

except for long-distance travel.

When traveling in the car I simply lay it on the passenger-side

floor, propped against the front seat, with the camera, flash, and

fresnel extender attached

(and a large towel laid over the lot, to hide it from unfriendly eyes

if I have to make a pit-stop along the way).

I tried putting it into the case and

stowing it in the trunk after every shoot, but since I tend to visit

several locations per day, this got to be too much of a hassle.

The lens is covered in a thick, black coating, which can be scratched fairly deeply without too obviously showing its wear. It’s been dinged, scraped, scratched, gouged, and even crapped upon (by birds, of course), yet with a little swab from a wet napkin the unit appears as pristine as ever. The front lens element is not (unlike Canon’s super-telephoto lenses) protected by any clear filter, but rather is left bare to the elements. This could, in theory, be detrimental in a saltwater environment, where corrosive elements could find their way onto the objective lens and do their harm to its anti-reflective coatings. After numerous trips to the Carolina coast, however, I can honestly report that no damage has been evident from the exposure of the lens to the elements. [UPDATE: After a year of use, the only damage I can see is a small cluster of micro-scratches, but you have to look at the glass in just the right light to see it]  Indeed, I can relate the following, fairly remarkable anecdote regarding this lens. While photographing a Common Yellowthroat in central North Carolina I noticed that the interior of the front lens element had fogged. This was, unfortunately, due to my having sprayed lens-cleaning fluid directly onto the glass (a no-no, as Sigma later informed me). Desperate to remove the fogging, I actually removed the frontal objective lens element (!) so as to allow the trapped moisture to escape, then replaced the front element and carefully screwed in the positioning hardware. This was all done on the spur of the moment, in the field, while the Common Yellowthroat curiously watched me from a distance of about 20 feet. Here’s an image of this bird taken with the lens while it was still fogged:  The alignment of the lens element was completely unaffected. Not only was the fogging gone, but the images taken subsequently were tack-sharp. Remarkable. The subsequent heron image below shows that the lens was unaffected by my in-the-field disassembly:  So, how does

the Sigma 800mm lens compare

to comparable Canon offerings?

Well, unfortunately, Canon has not (until very, very recently) offered an EF-mount 800mm autofocus lens. The closest thing has been either the Canon 600mm f/4L IS lens with a 1.4× teleconverter, producing an effective 840mm focal length, or the Canon 500mm f/4L IS lens with the same converter to produce a 700mm focal length. Although I’m planning to buy the 600mm lens soon, I’ve yet to perform a comparison with the Sigmonster. Such comparisons are relatively rare, since owners of one $6000 lens are unlikely to also purchase one of the other $7000 or $9000 lenses. From the few comparisons I’ve found on the internet, the Sigmonster appears to hold its own against the Canons mounted with teleconverters. [UPDATE: I’ve now performed this comparison myself. See the link below.] Note that the minimum focus distance is roughly the same for the Sigmonster and the Canon 600mm+1.4× TC combo (around 20 feet), and that there is very little difference in size, though the Sigmonster feels noticably lighter. Also, with the 1.4× TC attached, the maximum aperture of the Canon is reduced to that of the Sigmonster—f/5.6. One important limitation I’ve noticed with my Sigmonster is that in order to achieve maximal sharpness I have to stop down to a smaller aperture than f/5.6. At f/8 it is reasonably sharp, and at f/11 it is extremely sharp. Recently I’ve started using it at f/7.1 and have been quite satisfied. Some have made claims that the Canon 500mm and 600mm are sharpest wide open. Whether this is still true when a teleconverter is attached is not clear. If so, then the equivalent Canon rig at f/5.6 may blow away the Sigmonster at the same aperture. But that’s an “if”. I’ve yet to see convincing proof of this oft-bandied suggestion. It might, however, be true, and if so then that’s an important consideration when choosing between these (extremely expensive) products.  The Canon does come with a hardshell case, which might be useful when traveling by air. The Canons are also weather-sealed, which can be useful in inclement weather. I carry a folded wad of plastic trash bags in my pocket in case it starts to rain when I’m not close to my car. I’m not sure what happens to non-weather-sealed lenses that get thoroughly rain-soaked, but I’m guessing it’s a good thing to avoid. (On a side note, my Canon 100-300mm USM, non-L zoom lens recently rolled down a short incline into a pond. After a day of drying it was as good as new. Whew!). In May of 2008 Canon will be introducing its new 800mm f/5.6L IS lens, which will surely compete very favorably against the Sigmonster, and at that time the scales may indeed shift. The new Canon lens is expected to be extremely sharp, and considering that the Canon model features Image Stabilization (IS), which the Sigma does not, the Canon is overwhelmingly likely to produce more in-focus images in the field than the Sigma. Unfortunately, the street price of the Canon is expected to be around $12,000—twice that of the Sigma lens. Given the excellent result obtainable with the Sigmonster, it will be interesting to see how many Sigmonster owners defect to the far more expensive Canon offering, even if the price of the Canon eventually settles to the much more palatable, but still expensive, price of $9600 as some are predicting. [UPDATE: the Canon 800mm is now selling for about $14000 US, while the Sigmonster goes for $6000 or $7000.]  At

the end of the day, what matters is whether the tool you’re using

produces the results you expect or demand. For me, the Sigmonster

has done no less than open up a world of photography that was

previously unavailable to me. I can now, with reasonable effort,

capture scenes from the lives of wild birds—tiny, energetic, and

extremely restless birds no less—which, with the proper

photographic technique combined with sensible post-processing via

software, can produce images that in a previous life I could only have

dreamed of producing.

Will I ever upgrade to the Canon if it

ever comes down to a reasonable price?

Probably. Canon’s L-series lenses are pretty damned sharp, and with the IS built in, the chances of getting crystal-clear images only increases. But in the meantime, the Sigmonster remains my beast of choice. As the lusty month of April swiftly approaches, my thoughts drift ever toward that big, black creature lurking in the corner of my living room, waiting for its release into the sunlit mornings when it can hunt for its unsuspecting feathered prey. I truly relish the thought of being there when it makes its next “kill”. For me, that is the very definition of joy. All text and photos ©W.H. Majoros. All rights reserved. UPDATE: I have purchased a Canon 600mm f/4L and posted a comparison of this lens with the Sigmonster. Click here for the results.  UPDATE: My Sigmonster is now for sale here.  UPDATE: I now use a hand-held Canon 500 f/4L lens for almost all of my bird photography. Click here.  (photo by Caroline Gilmore) |